Coronavirus

02 December 2020

It is probably the strangest year of our lives. And as much damage as this coronavirus can still cause to public health and to 2021’s economy, 2020 is Covid year. Even if it’s second name is 19.

November and December in Portugal are just another good example of the uncertainty that we have experienced throughout this year. How many of us, living in the municipalities under the state of emergency, are able to list, without hesitation, the time slots when we are allowed to move around, and when commerce is open, for each day of the week?

Most of us have been living in uncertainty like never before. And there is only one thing worse for the economy than lack of certainty: the consummation of the fears that are at its origin.

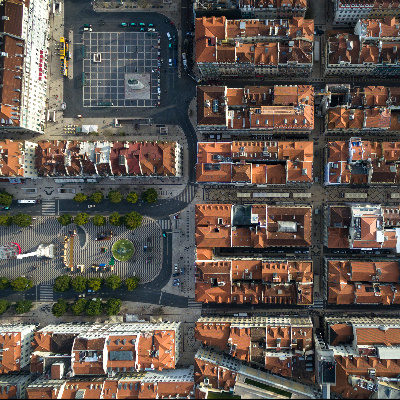

After a period of apprehension concerning the disease and its contagion, the greatest fear that the pandemic crisis managed to generate was the drop in income. The images of deserted cities all over the world reflected the downside of another reality: the world was at home and part of it was prevented from working.

The influence of the economy and political measures on real estate

One of the essential factors for analysing the real estate market is the state of the economy. If the capacity of a given activity to generate income is reduced or eliminated, the financial commitments of that business are not the only ones at risk. But also, the commitments of each of those whose income depends on that activity. On the same day that the state of emergency was declared in Portugal for the first time in this century, the suspension or renegotiation of rent from housing and commercial areas was already being discussed. This means, and this is nothing more than the acknowledgment of a fact, that the value of the properties was questioned since the first day of this crisis.

Another factor that equally conditions the real estate market: political measures and the respective legislative intervention. Its most obvious examples were the layoff mechanisms and debt moratoriums (loan payment breaks), whose impact on mitigating the effects of the economic stagnation was all too evident. These two measures do not work miracles. But they had the merit of avoiding a greater number of unemployed and preventing bank default. And they give us time. Time for public health solutions. But also, time for everyone to find solutions to their specific problems.

But like so many other resources, time is not endless. How much longer can the State sustain layoff mechanisms? If redundancies have affected, so far, mainly micro and small companies, the truth is that in the last few weeks there have been testimonies from some of the most popular law firms announcing that they have at hands collective dismissal procedures in large companies. The positive side is that in October, the month when the limitations on dismissals imposed by the simplified layoff regime ended, the evolution of unemployment numbers was less dramatic than what could be expected.

What about the moratoriums? They were extended until September 2021, but as of October this year, the Public Finance Council warned us of the possibility of State intervention to mitigate any bank losses. According to a DBRS report published in October, based on data from the end of June on 45 European banks (4 of the major Portuguese banks were analysed), Portugal is – by far – the country with the greatest percentage of moratoriums in its loan portfolio: 22% (the same figure that Banco de Portugal had already announced). Knowing that this data is related to June and that deadlines for joining the moratoriums have been continuously extended (until March 31, 2021, at this point) this number, already quite impressive, will surely grow.

That said, it remains to be seen how this data may condition, along 2021 and 2022, the availability of banks to continue to 1) finance the purchase of a house with up to 90% of the transaction/assessed value, 2) maintain current spreads (since September, there are banks providing rates of less than 1%).

Furthermore, according to a report published by the World Labour Organization, Portugal was the country - in a group of 28 European nations - that recorded the biggest drop in wages between the first and second quarters of this year, due to unemployment or the reduction in working hours.

On the other hand, low interest rates (and the perception that they will remain so for some years; Christine Lagarde's insight at the head of the European Central Bank seems to follow up on Mario Draghi's ideas), will continue to reflect a deficit of alternative investments. This may result in lower expectations regarding the return on real estate investment: the same clients who would mention gross profitability’s of 4%, 5% and 6% two years ago, nowadays may be satisfied with 3%. The question is: will they be willing to make investments without questioning the transaction values taking into account the current situation?

The importance of demography

Writings that have emerged throughout this crisis have suggested what seems to be more or less evident: that the economy and real estate in countries that are more dependent on tourism will suffer more severely. But let me share my optimistic belief concerning the national attractiveness: in recent years, Portugal has done more than become a tourist destination of reference.

Visit Portugal has been gradually turning into Moving to Portugal and the country has increasingly managed to assert itself as a place where people want to stay, not only for a few days or weeks but for an undefined period. And it is still relevant that, at a time when remote work reaches unimagined peaks in pre-covid periods, the international press starts to report some reluctance of expatriates and digital nomads in moving to the typical big cities (in this Bloomberg article you can find the usual paragraph dedicated to Lisbon and Portugal). That said, and according to the latest Immigration, Borders and Asylum Report by the Foreigners and Borders Service (SEF), the foreign population living in Portugal increased by 22.9% compared to 2018 (which had registered an increase of 13.9%, already much higher than that of 6% in 2017 and 2.3% in 2016).

It is true that more than 25% of the foreign community in Portugal is Brazilian, and that its number of residents grew 77% between 2017 and 2019, reaching a peak of 151,304 Brazilians in Portugal. And it is fair to suggest that this is due more to social instability in their country than to the merits of life here. But this trend does not limit itself to Brazil: although on another scale in absolute numbers (34,358 people), United Kingdom’s population living in Portugal increased by 30% between 2018 and 2019, being just over three thousand inhabitants of dethroning Cape Verde as the second largest foreign community in Portugal.

One thing is for sure, much more relevant than the number of clicks announced by real estate portals, the main indicator of house demand is the evolution of the population in a given area. And in a country where the natural balance (the difference between the number of births and deaths) remains negative since 2009, it was the migratory balance (the difference between immigration and emigration, which also accumulated negative values from 2011 to 2016) that, last year, guaranteed an increase in population – after 9 consecutive years in successive decline. Is this a tendency to stay?

And then, there is a whole universe of tops where Portugal seems to insist on appearing in the first positions, and that somehow contributes to its international marketing. From memory I can say that, in addition to the already well-known epithet of the third safest country in the world, granted by the Institute for Economics and Peace; the English Proficiency Index from Education First says that English is only better spoken in Holland, Scandinavia and Austria, something that strikes me as truly impressive. This is just to list two of the rankings that I found more reliable. I do not know how many others there are where Portugal is not at the top, and which we don’t know of because we are not there, but I increasingly believe in the idea of Portugal as a country that, in addition to those factors that everyone already knows about, such as the climate, food or goodwill, presents a competitive offer in terms of safety, urban lifestyle and infrastructures.

Having said all of this, I am of the opinion that house values have been decreasing residually since May (bearing in mind that, whether we are referring to the country or a parish, there is almost always room for diversity). And that much of the information that sustains the opposite, is either incomplete, or includes a significant number of deals that were closed with a down payment in the 1st quarter, even before the crisis took place, but whose deeds only occurred in the following months (the moment when the transaction is officially registered). In fact, according to the National Statistics Institute and in the 2nd quarter of this year (whose analysis must take into account what I just said about the time lag between closing the deal and formalizing its transaction), the median values / m2 per transaction decreased in 10 of the 24 Lisbon parishes (although they reached record values in 12 others). I believe that the official data for the third quarter will just confirm the obvious: the fall in prices is nothing more than the reaction of the real estate market to the social and economic paralysis caused by the pandemic. And that, obviously, this was not only more evident due to the political measures that were required, and to the maintenance of interest rates at historically low levels.

But it is important to remember the following: people's motivation to buy and sell a house stems much less from economic cycles than from their own life cycles. Much more than foster a desire, the economic environment either makes it easier or more difficult. That said, and without prejudice to the impact that a state of emergency has on the number of real estate transactions (as on a million other things), people will continue to go on with their lives – for as long as they can. And that also means continuing to buy, sell or rent houses. And to say that prices are falling is not announcing a crash. It is just to recall that when a large part of the world is losing money (or earning less than it had expected), and when mobility is so compromised, it would be surprising that house values would continue to rise.

National governments and the European Union (regarding the latter, like never before in their history) will be well aware of the need to mitigate the loss of income and prevent bank defaults. Sooner or later we will measure the degree of their success. And if so far, the government's focus has been to prevent widespread unemployment ... it is to be expected that they will start considering proactive employment measures to promote hiring, a kind of New Deal of the 21st century.

But speaking about success in the struggle against the economic damage of the pandemic, without bearing in mind that all this is, first of all, a public health crisis, will always seem like ramble. We can only hope that the vaccines that have generated so much euphoria in recent weeks will prove to be everything that is expected from them.

And it may not seem so, when compared to much of what is read in the real estate sections of the press, but this is an optimistic text.

_3140.jpg)