Investment

04 November 2020

Public debate regarding golden visas is held hostage by two parties that seem to have given up trying to find the most balanced solution for the country. And arguments from both sides seem to essentially follow their own agenda and field of interests.

The delusion

In statements to Newspaper Eco, Eric Van Leuven, Cushman & Wakefield’s Director Head of Portugal, explains why golden visas wouldn’t have had a significant impact on housing prices and rents: “When the scheme was launched in 2012, prices increased slightly because there were houses on the normal market that were worth 400,000 euros, but for a visa holder they jumped to 500,000 euros. Visas themselves, however, were not responsible for the price rise”.

I

I will sidetrack the philosophical reflection on what "slightly" may mean to Mr. Van Leuven, and think about what I would need to do if I wished to buy a house that "was worth" € 400,000, but for which there were buyers willing to pay € 500,000. That said, it seems to me that if there are or were people paying 25% more for a house because it’s value has been artificially inflated, there could be no better reason for a government to want to end golden visas. We can (and should) discuss whether this example is representative of what happened. And reflect on how hilarious it is that this scenario is presented by someone who claims that golden visas have not impacted prices. And while we’re at it, consider the carelessness of what is said by market agents and the total lack of critical awareness in a type of journalism that provides a stage for these kinds of comments.

II

There seems however to be a slight subtlety in Mr. Van Leuven's speech. I will repeat it: "there were houses on the normal market that were worth 400,000 euros, but for a visa holder they jumped to 500,000 euros". Whatever does he mean by this? That the advertised price of a house varies according to the interested buyer? That we charge an additional 25% to foreigners?

I believe I can try to explain what Mr. Van Leuven seemed to be thinking but did not elaborate, and that the journalist did not find pertinent to ask ...

To date, more than 50% of golden visas have been granted to Chinese citizens. At the end of 2014, this figure exceeded 80%. For reasons that seem easy to understand, a Chinese citizen may experience some difficulties checking the sites of national portals and real estate agencies. There is no data to confirm what I am about to say, but it is commented among real estate agents that during the first years of the scheme, properties available on the market for lower prices were sold to Chinese buyers for € 500,000.

Imagine houses that were being advertised for € 400,000 or € 450,000, but that had documents in Mandarin made available to potential Chinese buyers, where the price shown would be around € 500,000. In other words, properties that, in a transparent and informed market, would never be traded for half a million euros. But that, presented to Chinese investors, who had difficulties in checking the market for themselves and were poorly advised, were purchased for these values. Because (almost) everyone would have something to gain.

The owner would benefit and significantly increase his profit even if, potentially, he paid the broker 10% instead of 5%. The real estate agent, who, even if he had to give 3% or 4% to a Chinese intermediary would retain 6% or 7% of € 500,000, instead of 5% of € 400,000 or € 450,000. We can argue (can we really?) whether the investor, focused on obtaining a residence permit, will also have benefited. But I think we all agree that none of this was positive for Lisbon residents searching for houses in central areas of the city, or for the sector’s transparency.

Of course we are in 2020 and posting #blacklivesmatter on social networks is all we need to demonstrate to the world that we are cool and respect everyone, regardless of skin colour or country of origin. But what I would really like would be to have been in the journalist’s shoes, to question Mr. Van Leuven on his definition of "slightly", how slight is 25%, and whether he thinks it’s credible that someone whom nobody lied to or omitted relevant information from, pay € 500,000 for properties that, according to himself, "were worth € 400,000".

by sunakri

The convenience of political measures. Even when they seem misplaced in space and time

Around 90% of the 5.5 billion euros raised via golden visa in recent years entered Portugal through the purchase of real estate.

One of the most discussed issues against golden visas and the one generating the most pressure and political media coverage against the program’s current regulations, is the significant increase in house prices. Just for you to be aware of: between the 1st quarter of 2016 and the 2nd quarter of 2020, and according to official data, the median value of the square meter increased 80% in Lisbon and 75% in Porto (and 37% in the whole country, value leveraged by the two largest metropolitan areas). These are exciting numbers for any investor who, half a dozen years ago, decided to purchase real estate in the country’s two largest cities. But they are also truly scary numbers for anyone living in the two largest Portuguese cities.

Let's be clear: when the Residence Permit for Investment Activity (ARI) program came into effect in 2012, a € 500,000 house was practically a luxury anywhere in the country. But with the price evolution in Lisbon and Porto, it has become a requirement for a significant number of families. Given such an increase in house prices, and with significant reason to believe that one causes the other, wouldn't it have been much more useful to change the minimum value allowed when granting residence permits? And this is in what regards the municipality of Lisbon which seems to have been, since the beginning of the program, the most popular location by those who applied for a golden visa (the case of 60% of those who, between January and September of this year, obtained a golden visa via real estate investment).

If the overvaluation of houses is this government’s genuine concern, and if there is data to correlate a greater demand for properties of a certain value in Lisbon, due to the granting of golden visas, the government could and should have already increased the minimum investment amount. Especially because, if the concern is actually the Portuguese citizen's capacity to meet purchase prices, it is curious that this change is being considered for the first of many years, where there are no prospects of house prices increasing in Lisbon and Porto.

It seems to be no surprise, however, that political marketing so often gains precedence over the fundamentals of political measures.

The context in which golden visas emerged

Golden visas came into force in October 2012. It is important to remember that, in 2011, the lack of control of sovereign debt and the increase in interest rates that asphyxiated Portugal, led to the resignation of the then prime minister and the request for foreign aid. It is equally important to remember that, at that time, the end of the Euro or Portugal’s exit from the single currency were topics that were mentioned by the press more often than we would all like. And the simple suggestion of a scenario where we returned to the Escudo did not only frighten foreign investors: there were Portuguese citizens thinking that their money would be safer in German banks. Remember, by the way, that these were the years where the term “rating agency” appeared in the headlines often to tell us how close to “trash” we all were.

Portugal needed to reduce expenditure without penalizing the economy. Attracting foreign investment was not only logical. It was necessary.

On the other hand, it must be noted that granting residence permits in exchange for investment is a discriminatory measure: some are offered what is refused to others, solely and exclusively based on the amount they are willing to pay. And I think it’s healthy for us to at least reflect on the following: obtaining a residence permit on these terms, is similar to entering a nightclub where, if you have reserved a table with half a dozen bottles of champagne, you are allowed to skip the line at the entrance.

The truth is that in eight years Portugal has gone from a country where it did not seem safe to invest your money, to the frontline in terms of investment. This change is due to a set of measures and events that had significant impact on the existing perception of the country, its capacity to deal with external debt, and economic buoyancy. And yes, residence permits for investment (golden visas) are an important part of this transformation.

by Balate Dorin

Linking of databases between SEF and INE

According to the Immigration and Borders Service (SEF), in 2019, and out of a total of 1245 authorizations, 1160 golden visas were granted through the purchase of real estate, corresponding to an investment of 661 million euros. This represents an average of 570 thousand euros of investment per residence permit. Which, without prejudice to the existence of types of access to residence permits for lower values, and knowing that the required amount may concern one or more properties, seems to confirm what common sense suggests: that houses around € 500.0000 are the main target of these investors.

Still in relation to 2019 and now according to the National Statistics Institute (INE): 19,520 properties were purchased by non-residents for a total of 3,444 million euros (13.3% of the total volume of housing transactions in Portugal last year). This allows us to draw the first conclusion: golden visas represent 19% of the total investment of non-residents in housing and 2.6% of the transaction volume in the residential segment in Portugal. *

But INE did something even more interesting, counting how many of these properties had a transaction value greater than € 500,000. In 2019, 1462 were purchased by non-residents, which represented 1,349 million euros for an average transaction value of € 923,000. But since we know that the average investment of the 1160 visas granted through real estate investment was 570 thousand euros, we can draw two conclusions:

• that close to 79% of properties over half a million euros will have been purchased by people who have been granted a residence permit for investment *

• that the remaining 21% will have purchased the most expensive houses.

* see final note

by PeekCC

Conclusion

The government should explain and share, in a clear and transparent way, data to support the concerns that served as an argument to change the formula that ensured, over 8 years, an investment of 5 billion euros. Whether referring to difficulties in accessing housing, fears regarding the origin of the invested capital, or any other reason.

There is something interesting which is important to bear in mind. Before, I wrote that the increase in values per square meter in Lisbon and Porto leveraged the national real estate numbers. But there is a note that no one refers to: since 2019, the value of the square metre in Lisbon and Porto has evolved below the national average. An indicator that real estate investment in large urban centers is starting to shift to more peripheral areas (probably, not further away than the respective metropolitan areas). To be able to carry that domino effect to the interior would, admittedly, be a remarkable achievement.

But it is important to be realistic. Excluding the coast from eligible areas can drive investment away. Extending the range of options, scaling the acquisition amounts in a more differentiated way would, I believe, be the best way to encourage foreign investment in the interior, without losing those who insist on staying in Lisbon or the rest of the coast. As long as they are willing to pay amounts that do not conflict with social balance. Because you must take care of those who have always lived here. And because this balance is responsible for attracting as much or more investment than the golden visas themselves.

* Final note: estimations presume that each residence permit issued in 2019, corresponds to one or more real estate transactions in the same year, which is not necessarily true (the transaction may have happened in 2018 and the residence permit issue in 2019 or a 2019 transaction may have resulted in a residence permit grant in 2020); but since the number of granting authorizations did not vary by more than 13% between 2018 and 2019, and granting of golden visas in 2020 points to a final annual number among the values recorded in the two previous years, this was a way of trying to correlate data from INE and SEF without, apparently, incurring in a great risk of bias.

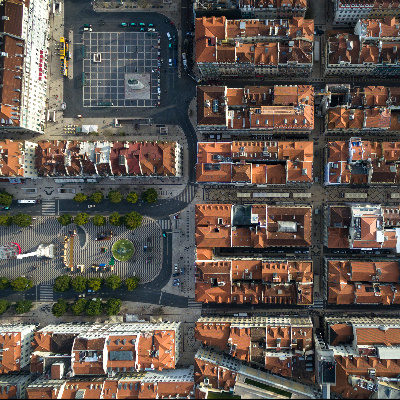

Lisbon grelha_4577.jpg)