Economy • Credit

02 November 2019

The Italian’s mandate as head of the European Central Bank (ECB) ended on the 31st of October. And his legacy did not only interfere with the accounts of European governments. Mario Draghi’s expansionist policies at the head of the ECB have had a very significant impact on the personal and family budget of many Portuguese (and other European) people. Particularly on the monthly expense of those who have housing loans.

Mario Draghi took office as President of the ECB on 1 November 2011. That same month, he lowered the reference interest rate from 1.5% to 1.25% and, the following month, he lowered it again to 1% (which has remained at 0% since 2016). The reference rate is the interest rate at which a central bank lends money to a commercial bank, which in turn lends money to individuals and businesses. Now, if the interest rate applied to banks goes down, it is expected that the interest rates they apply to their customers will eventually fall as well. This can impact your accounts in two ways. If you have variable interest rate loans, your bank payments will go down. If you have resources, interest paid by financial institutions for your savings or investment applications will tend to fall as well.

Let us recall the context in which Draghi took over the presidency of the ECB. Do you remember the European Troika? In those days Greece and Ireland (2010) and Portugal (2011) had already requested foreign aid, with Spain and Cyprus having to do the same in 2012 and 2013. This means that the governments of these countries – independent and sovereign nations – recognized before voters, investors and other states that, in the near future, they might fail to pay their responsibilities. It is clear that a country at risk of defaulting on suppliers or failing to pay salaries to public officials inspires little confidence. Now, the cost of a given financing varies in inverse proportion to the perception of risk it inspires. This means that the interest rate charged to our country and our banks was high. Consequence? Borrowing from a credit institution in Portugal was not easy and the loans granted were made by applying unattractive rates.

Draghi’s Legacy

The truth is that foreign aid mechanisms have helped countries like Portugal to gradually regain the confidence of investors who, at that time, seemed more comfortable with the idea of investing in countries such as Germany. In the face of a hypothetical collapse of the Euro, the prospect of keeping German marks in your wallet seemed more enticing than collecting Portuguese escudos or Greek drachmas. In this way, it was possible to lower the interest on public debt and the financial burden on loans 1) from the Portuguese State, 2) from national banks and, 3) therefore, from Portuguese people as well.

To get an idea of what was happening: on 31 January 2012 and according to the Bank of Portugal (BP), the average interest rate on mortgage loans was 4.68% in Portugal and 3.77% in the Eurozone. And to get a sense of how much this reality has changed, on 30 September 2019, still according to BP, those same values were 0.95% for Portugal and 1.47% for the Eurozone. In between, Draghi speaks out his famous "Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the Euro". These statements had a brutal impact on the perception of what could be done to attest to the soundness of the single currency. Following this, the ECB implemented a series of measures, of which I highlight the following:

1) Injecting money into the economy through medium-term financing operations to banks so that these can, in turn, provide liquidity to businesses and consumers (more money available to lend to the people and easing of the conditions under which the funding was granted). Sounds vague? In 2018 alone and according to BP, it was granted 96% of the mortgage loans that had been made available in 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 together (158% of the amount granted between 2012 and 2014).

2) Stimulating the economy through the purchase of public debt. By buying debt from Portugal and other countries with less financial clearance, the ECB contributed to an increase in the demand for these securities. Demand for a given product or service has an appreciation effect on that good (for example, if more people are interested in buying your house, our perception of its value tends to grow). In this case – since we are talking about debt – (a country receives a portion of money from an investor and commits, over a certain period of time, to repay the capital and pay interest on it) – the perception of risk on that same loan decreases, and therefore its interest rate as well. This means that Portugal managed to reduce expenses on its borrowing costs (according to Expresso, Mario Draghi’s action will have saved our country 7.4 billion Euros in 5 years.)

So yes…. If you have money in the bank yielding close to zero, you have every right to hold Mario Dragui responsible for it. But remember that it is also thanks to the action of that Italian economist that it is possible to pay 1% of TAN (euribor + spread) on a loan to finance the purchase of a house. This is due to the fact that euribor has evolved into negative values. But also because the spread charged by banks has dropped significantly. And both changes are also the result of Draghi’s action.

But Draghi’s measures can generate even more impact on the lives of some Portuguese people... (or foreigners who live here)

Fixed or variable interest rate?

The widespread decline in interest rates and the fact that this scenario is expected to last throughout the following years marks times of financial clearance for many families in Portugal. On the other hand, mortgage loans are traditionally long-term financing (20, 30 and 40 years). This means that it is impossible to predict what will happen to interest rates in 2025, 2030 or 2040. Imagine that in the next 10, 20 or 30 years, interest rates will not return to values as low as they are now? Is it worth fixing the rate and being penalized in the short term for a higher monthly installment, hoping that, sometime in the future, a predictable rise in the rates would save you dozens or hundreds of euros a month? Maybe….

Now, it is important to remember the following: not only it is impossible to predict the evolution of interest rates but sometimes we cannot even predict what happens in our own lives. A job proposal for a different city or country, the unexpected birth of one more child or a separation are all events that might lead to a change of house. In face of this scenario – paying off your mortgage earlier than expected – sacrificing the present to focus on hypothetical gains in the medium-long term may prove to be a failed option. Not to mention, in Portugal, the maximum amount that banks can charge for a fixed-rate house loan early settlement commission is four times higher than what they are allowed to charge when financing is granted through the application of a variable interest rate.

Renegotiation or mortgage transfer?

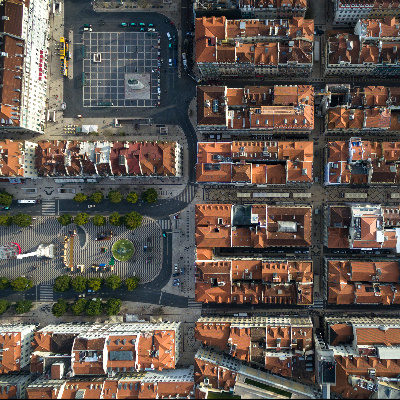

In recent years we have not only witnessed a fall in interest rates in the Eurozone. Across most of Europe we saw house prices rise (according to EuroStat, only Ireland, Spain, Italy, Cyprus and Greece haven’t yet been able to recover 2008 figures). Just to get an idea of the Portuguese example: the housing price index of the National Institute of Statistics rose more than 53% between the 2nd quarter of 2013 and the 2nd quarter of 2019. This means that many of the people who bought houses before 2014 saw the commercial value of their real estate soar. That is, they bought real estate for much lower values than those that are practiced today but with significantly more adverse financing conditions than those that can be agreed in 2019. Today, they would have to spend a lot more on the purchase but would face a significantly lower value of money. Can these people have the best of both worlds?

A more affordable credit for a purchase that, in light of today’s values, almost appears to be on sale? In theory yes. We have to bear in mind the expenses that may entail a renegotiation or credit transfer, but in fact the current conjuncture allows more attractive financing conditions. A mortgage credit approval process essentially deals with 3 variables: financing amount, relation between that same amount and the value of the collateral (the property will always be subject to a new evaluation), and the clients’ ability to meet monthly repayments. Assuming that proponents’ incomes are not lower than at the time of the original financing (or that their liabilities to credit institutions have not skyrocketed), the other two variables will tend to benefit you because, although the house is worth more, the amount needed for its finance continues to refer to the original purchase price. That is, the relation between the value of the property and the financing will most likely go down significantly. And, in this way, the bank’s risk perception as well. Not to mention (because it deserves to be repeated) that interest rates on credit operations have declined significantly in recent years.

Bye-bye Mario, hello Christine

Portugal and (most) Portuguese people have reasons to feel grateful to Mario Dragui. Now it is the turn of Christine Lagarde, former managing director of the International Monetary Fund, to take over the ECB presidency. During Draghi’s mandate, the French politician, economist and lawyer praised many of his measures. In the short term, no significant changes in the policies of that institution should be expected. But opposition from countries that, due to the sharp fall in interest rates, pay interest to lend money, (or so many of us who are fed up with having money in the bank and not getting any return) is likely to gain more and more voice.